As a new film celebrates the legendary post-Woodstock tour, and its tribute concert, Jim Farber talks to original performer Rita Coolidge and director Jesse Lauter about ego clashes, bust-ups, jealousy and why Cocker went off the rails

More than 50 years have passed since the tour known as “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” tore its way through America, leaving a legacy that’s at once starry and troubled, vaunted and pained. “That tour just wore me out,” says Rita Coolidge, whose appearance on it led to a highly successful solo career. “I don’t think anybody could have survived another trip out like that. They would have been dropping like flies.”

At the same time, Coolidge says, “many days I wake up thinking about that music and how amazing it all was.”

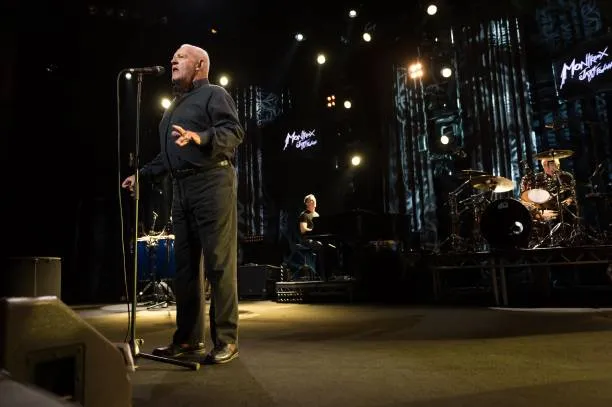

Small wonder the “Mad Dogs” tour – fronted by Joe Cocker and backed by a cast of nearly 50 singers, players and hangers-on, including classic rock linchpins Leon Russell, Bobby Keys and Jim Keltner – became enshrined as one of the most exciting live events of all time. It’s legendary enough to have inspired a 2015 tribute concert, led by current US stars Derek Trucks and Susan Tedeschi, which boasted many of the surviving artists from 1970, including Coolidge and singer Claudia Lennear, pianist Chris Stainton and creative czar Russell, who made his last major appearance at that show, before his death in 2016. Now, five years later, director Jesse Lauter is releasing a new film, Learning to Live Together, which weaves together footage from the original show with musings and music from the tribute concert. “I tried to make clear the beautiful link between the old show and the new one,” says Lauter. “I also wanted to show how the original show changed the course of rock’n’roll history.”

It had an equally transformative effect on the lives of many who took part in it – though not always for the better. On the one hand, “Mad Dogs” made Russell a household name, boosted Keys into a regular sideman position with The Rolling Stones and turned Keltner into one of the world’s most in-demand drummers. It also yielded a double live album that shot to No 2 on the charts, boosted by two major hits, “The Letter” and “Cry Me a River”. On the other hand, “Mad Dogs” killed friendships, ruined romantic relationships and left Cocker, its star, penniless, drug-addled and creatively at sea. More, there was violence backstage, as well as threats of it that date back to the tour’s birth.

From the start, “Mad Dogs” was chaotic and fraught. In March of 1970, Cocker was riding high after his soul-shaking performance at Woodstock the summer before. To take advantage of the momentum, his management demanded that he throw a tour together at lightning speed – not an easy feat since he had just fired most of his backing group, The Grease Band. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the kind of demand you could ignore. Cocker’s manager, the late Dee Anthony, has often been depicted as having been mob-connected, a view supported by the recent memoir by another of his former clients, Peter Frampton. “We would make jokes about that and push our noses to the side like you do when you talk about the Mafia,”

With the implicit threat of “tour or else”, Cocker turned to Russell – a well-connected multi-instrumentalist who had produced his most recent studio album – to find great musicians pronto. To do so, he plundered a band led by Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett, swiping from them Keys, Keltner, Coolidge and the duo who would later form the rhythm section for Derek and the Dominoes, Carl Radle and Jim Gordon. Though Delaney and Bonnie’s original group never became big sellers, they played a crucial role in music history. In 1969, they were the only white band on the storied Stax Records label. Their album on that imprint proved so powerful, it inspired no less a line-up than Clapton, George Harrison and Dave Mason to join them for a historic 1969 tour of the UK, which yielded an ecstatic live album, On Tour with Eric Clapton. In addition, Russell’s piano work for the duo proved pivotal to a then unknown Elton John. “Elton once told me that if it weren’t Delaney and Bonnie and Leon he never would have done what he did,” Coolidge recalls.

Miraculously, Russell whipped together the Mad Dogs band in just eight days, stuffing it with as many people as possible. In the film, Russell says his inspiration for the mass casting was the hippie love-ins that featured scores of musicians and chanters who created a cacophony that somehow ended up sounding sweet. The quest for such a sound had a thrilling effect, enhanced by two powerful drummers, a Latin percussion section, a pumping horn trio and a “Space Choir” of singers who echoed the sound of a gospel chorus. Still, the pile-on had a down side. Some in the Space Choir couldn’t even sing. “As choir leader, sometimes it was hard for me to get some of the people who were not singers off the microphone,” Coolidge says.

As a result, the live album from the tour required major remixing and vocal enhancements. Regardless, the result brought something new to music by marrying big band R&B of the 1940s with Sixties rock’n’roll. “They were probably the first of the rock’n’roll big bands,” Lauter says. “That set off a whole trend.”

You heard it on Clapton’s self-titled solo debut in 1970, which also featured much of the Delaney and Bonnie band, as well as the giant group George Harrison assembled for 1971’s “Concert for Bangladesh”, which employed some of the same musicians as “Mad Dogs”, and Dylan’s sprawling “Rolling Thunder” tour in 1975. Russell actually name-checked Dylan on the Mad Dogs album as an audience member before he and Cocker performed his yearning ballad “Girl from the North Country”.

To up the theatricality, Russell encouraged the musicians to dress and act as outrageously as possible, creating a circus-like atmosphere for which he played ringmaster, outfitted with a Captain America suit and a top hat. Unfortunately, such a defining role for Russell wound up alienating the event’s ostensible star. “It got to the point where Joe didn’t feel like it was his tour,” Coolidge says. “He felt like he was not in control and, consequently, he would just take any drug that anybody handed him and then he really wasn’t in control.”

To a listener, however, Cocker’s wrenching soul cry and the band’s manic back-up seem like they were born for each other. Together, they created a gripping amalgam of rock, soul, gospel and blues. “It was classic, cosmic American music,” says Lauter. More, their repertoire, which featured songs penned by everyone from The Band to Isaac Hayes to The Beatles, contained what Lauter calls “the most sacred music in rock’n’roll history”.

Coolidge got her own showcase on the tour by fronting the soul ballad “Superstar“. Though the song is credited to Russell and Bonnie Bramlett, Coolidge says she had instigated the writing. “Somehow when it came out, my name wasn’t on it,” she says. “I know Bonnie would never hurt me but I think Leon had hard feelings and just said ‘screw her’.”

Coolidge, with whom Russell was romantically involved and for whom he wrote the ravishing ballad “Song for You”, left him before the tour to take up with drummer Jim Gordon. “Leon adored Jim so he took it all out on me,” Coolidge says. “I left him and he wasn’t used to that.”

Unfortunately, her alliance with Gordon led to something far darker. One night while on tour, without warning, the drummer called her into the hallway and proceeded to “beat the shit out of me”, Coolidge says. “He was out of his cracker box.”

Years later, the drummer wound up killing his mother. Only afterwards was he diagnosed with acute schizophrenia. “When he was arrested, he said that he had also planned to kill his ex-wife but he was too tired from killing his mother,” Coolidge recalls with a dark laugh. “He wouldn’t have been done killing. I think if he were out now, he still wouldn’t be done.”

After Coolidge was attacked, she wanted to leave the tour but Cocker convinced her to soldier on. “I stayed for my love of him,” Coolidge says. By the tour’s end – after a punishing 48 dates in just over two months – everyone was either worn-out or strung-out. The massive cost of the show, which included flying the cast around in a private jet, left the star himself without a dime. “I probably made more money from that tour than Joe did,” says Coolidge. Afterwards, “he was living at (producer) Denny Cordell’s house and sleeping on some kind of mat by the front door. He didn’t have money to buy a guitar. But for him it wasn’t about the money. It was more about him feeling that he had been betrayed and that everyone profited from it more than him.”

In the film, Russell talks about being warned that he would be accused of “career profiteering” and of spending all of Cocker’s money on the pricey backing musicians. But, says Lauter, “Leon wasn’t scheming to profit off Joe. Leon told me, ‘Look, I’m just the band leader.’ He had this idea for the big band and at the beginning Joe was gung-ho about it. The tour was put together very quickly so maybe it takes you several weeks to realise, ‘Oh crap, what did I get myself into?’”

Still, the scale of the project turned out to be a key part of its legacy. Five decades later, it inspired Trucks and Tedeschi to form a big band of their own, The Tedeschi-Trucks Band. “The Mad Dogs band was pivotal to us,” Trucks says. “They were like the white Sly and the Family Stone.”

Consequently, in 2014, when the organisers of the jam band-oriented US Lockn’ Festival approached The Tedeschi-Trucks Band about forging a collaborative live project, they first thought to contact Cocker. Unfortunately, he was sick at that time. (Cocker died of lung cancer at the end of 2014). For a substitute, Trucks turned to Russell to explore a Mad Dogs salute. “At first, I thought maybe this wouldn’t be something he would want to jump back into,” Trucks says. “But he was so excited. I think it was a way for him to put that thing to bed, or to confront it, or to have the reunion he never got to have.”

With Russell on board, many of the surviving members of the original show happily signed on. They even managed to rope in Dave Mason, formerly of Traffic, who didn’t appear the first time but who wrote a key song that was performed there, “Feelin’ Alright”. Even so, Trucks knew that trying to reinvent a classic show had risks. “Forty or 50 years down the road, there’s no way it’s going to be the same thing,” he says. “But it became its own thing.”

The insertion of Trucks’s style into the Mad Dogs’ mix wound up forming a modern connection between that band and its original sonic relatives, including Delaney and Bonnie, Derek and the Dominoes and The Allman Brothers (with whom Trucks played for years). “One of the reasons I felt it was OK to take on this project was because of all those historic connections,” Trucks says.

In the film, the older musicians express deep appreciation for getting the chance to recreate music that had changed their lives. For Coolidge, the new show actually trumped the old one. “This time it was grown-ups instead of kids,” she says. “That makes a difference.”

“The original show probably had to be insane to become what it was,” Trucks says, with a laugh. “But there’s an upside to being able to look back now and say, ‘this aspect of the tour was magic, but this aspect was never going to end well.’ This time, we just took the magic.”